| If you do

NOT see the Table of Contents frame to the left of this page, then

Click here to open 'USArmyGermany' frameset |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

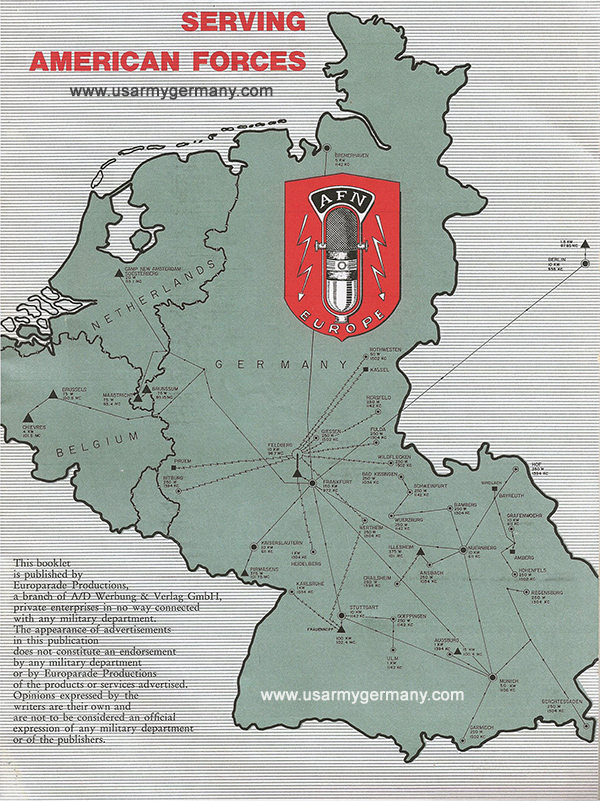

Armed

Forces Network, Europe |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

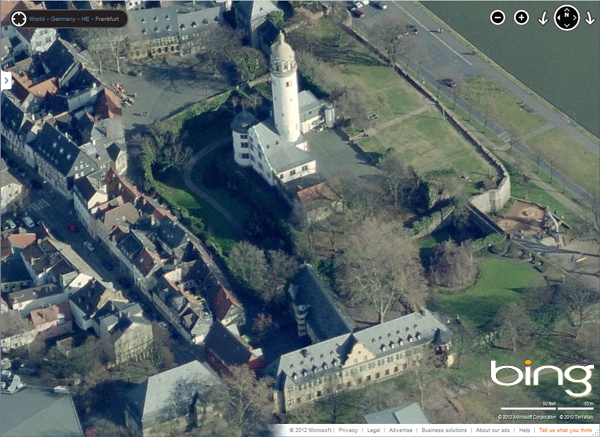

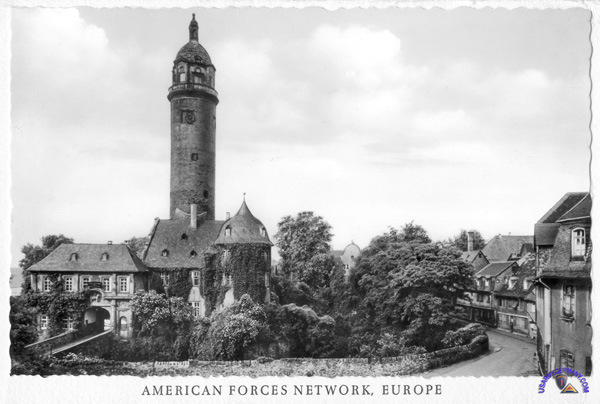

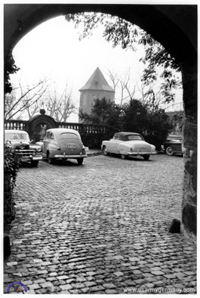

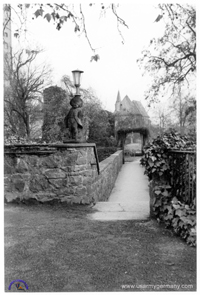

Entrance to AFN-Europe Headquarters at Höchst, 1959 (Frank da Cruz) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1945 - 1983 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: "40th

Anniversary, AFN", AFN TV-Guide, July 1983) The following persons provided original materials incorporated in the History of AFN as it appeared in the July 1983 issue of the TY-Guide: COL Ted Shoemaker; Mr. Robeut J. Harlan; Mr Don Brewer; LTC Robert P. Bubmak; AFN was thanked for the use of its historical archives; as were numerous staff members of AFN for their generosity, in sharing their memories; and several unknown but highly appreciated authors who compiled earlier versions of the AFN history; AFN Commander LTC Charles R. Crescioni was thanked for his support; as well as Mr Trent Christman who tried to separate the wheat from the chaff and pull the whole thing together but mostly, and all AFNers-pastand present - who by their very presence had contributed so much to this history. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

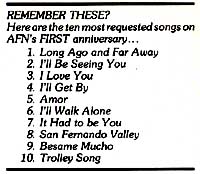

In spite of a glut of news to fit into the few pages available, editors featured three-fourths of a column on the front page headlining the start of a new radio service for United Kingdom-based troops. There can be no doubt that it was a start, but looking back from the perspective of forty years it can be debated that it was a service. Not, at least, for the first few faltering weeks when the broadcast day consisted of less than five hours of recorded shows, a BBC newscast and a sportscast read by an AFN announcer but supplied and written by Stars & Stripes. The mere fact that the broadcast infant was squalling on the airwaves for even five hours a day is a miracle, almost as great a miracle as the fact it continued to thrive and grow in size and importance for the next forty years. To understand the beginnings, it's necessary to go back to those early war years of 1941 and 1942. There were a few primitive military broadcast operations already in existence. Kodiak, Alaska, had started the whole thing because gung-ho Signal Corps troops built a transmitter and began playing records. Thule, Greenland, had a home-made station also - called KRIC which, the staff explained, stood for "Kee-Rist It's Cold." It soon became obvious that there had to be some sort of order to military broadcasting, particularly supplying music and programming from home to be played for the troops overseas. The need was filled by the formation of AFRS, the Armed Forces Radio Service, in 1942. AFRS added a "T" for television many years later and to this day continues to do the job for which it was designated on a scale never dreamed of in those early World War II days. As America mobilized its forces for worldwide conflict, troops poured ashore in Britain and Northern Ireland for training and eventual invasion of the continent. So many troosp and so much equipment came ashore, in fact, that the British claimed the only thing keeping the islands from sinking into the sea were the barrage balloons. The troops were eager and ready to fight. They were also lonely and homesick. The idea of a GI radio operation first saw the light of day in an early-1943 meeting between Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall and Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. They decided a voice from home featuring the radio programs the troops were used to, news and U.S. sports would help fight loneliness and homesickness. When two men with eight stars decide something should be done, something is done. AFN sprang into existence. Perhaps "sprang" isn't exactly the word. "Crawled quickly" might more accurately describe what happened. Lieutenant General Jacob Devers, Ike's chief of staff, took the ball handed him by his boss and passed it on to the best man he could find to get the job done, a young captain named John S Hayes. Hayes, who had a background in civilian radio, suddenly found himself the first AFNer although at this point the network not only didn't have a name, it didn't have a studio, a transmitter, a microphone, a turntable, a staff, a filing cabinet, or a listener. It had a targeted completion date, though: 4 July 1943. Now there were eleven stars pushing for completion; powerful motivation for a young captain. Somehow, in the chaos of wartime London, he wheedled office space and a secretary. For clout he turned to the Office of War Information. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Brewster Morgan, radio chief of the OWI and Richard Condon, OWI's

chief engineer, offered to help. Between them they got the BBC to

waive its monopolistic rights to broadcasting in the United Kingdom.

When they got Britain's Wireless Telegraphy Board to give its blessing, AFN, though certainly a small child, was suddenly legitimate. The BBC offered its own cramped emergency facilities at 11 Carlos Place, London, just off Grosvenor Square. It was from these studios that Edward R. Murrow was making his famed "This is London" shortwave reports to America each night and from which the BBC itself occasionally broadcast during the height of the blitz. There were no computerized personnel records in those days and it took Captain Hayes and Army personnel clerks three weeks of combing records before they came up with twelve experienced radio people. Finally it was 5:45 p.m. July 4, 1943. Hayes no doubt breathed a sigh of relief as the network signed on to the strains of "The Star Spangled Banner." Listeners on that first evening heard the Bing Crosby Music Hall, the Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy Show and the Dinah Shore Show crackling through the air from five 50-watt transmitters located in troop concentrations throughout the British Isles. This was a period of explosive growth. D-Day was 11 months away, but troops were pouring in by the shipload. AFN grew, too. The broadcast day was gradually lengthened to 19 hours daily. More than 50 transmitters were installed, including six in Northern Ireland, all linked to the temporary London studios at 11 Carlos Place. Personnel were added to handle the additional air time and engineering duties including Corporal Johnny Vrotsos who stayed around (later as Mr. Vrotsos) to become over the next twenty years AFN's best known personality. Many longtime AFN listeners still fondly remember Johnny Vee. Preparations for the invasion of mainland Europe had reached a crescendo by May of 1944 - and so had the V-1 rocket bombs. AFN staffers didn't particularly like being knocked off the air by buzz bombs landing near Carlos Place, so as May rolled around no one was sorry to move to 80 Portland Place. Besides, it also gave everyone a little more room. The D-Day preparations included plans for a combined broadcast operation to include AFN, the BBC and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The mobile broadcast vans were prepared, and AFN staffers accompanied the allied troops as they stormed ashore in France on the 6th of June, 1944. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Although the shooting has long stopped, this kind of dedication to the job continues after 40 years. As recently as 1982, two AFN staff members - Airman Mike Sutton and Private Bruce Scott - lost their lives in a helicopter crash near Mannheim, Germany, while covering a story for AFN Television.

The mobile units broadcast music and news to the frontline troops and fed news reports back to studio locations as well. The First Army unit scored a newsbeat on the whole world when First Army Commander LTG Courtney H. Hodges dropped in to announce the capture of Cologne. While the armies were moving into Germany, troops were being stationed in liberated France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. It was necessary to provide radio service to these men and women as well and the now rapidly expanding AFN began putting more and more stations on the air. Radio people have never been particularly noted for their modesty and the predecessors of today's AFNers were no exception. War may, as General Sherman said, be hell, but its hellishness was lessened somewhat when AFN studios were opened in Paris. No cramped basement quarters this time. They were in for mer Emperor Napoleon III's Parisian palace. These elegant digs became the operating headquarters for the network although the administrative headquarters remained in London. With Paris as a hub, other stations were opened in such hard-to-take locations as Nice, Cannes, Biarritz, Marseilles and Le Havre. And Reims. The guys that chose Reims weren't modest either. They opened the station in the De Polignac castle which happens to be the home of Pommery champagne - nine million bottles of which were stored in the basement. At least there were that many when they moved in. No record exists of the inventory when they moved out. The good life in France ended in 1946 when all these stations closed. It would not be until 1958 that AFN would return to broadcast again from French soil although never again from such lavish surroundings. The wartime period saw some of the finest entertainment - and entertainers visiting or working in front of the AFN microphones. Just a few to visit the London studios were Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Jerry Colonna, Marlene Dietrich, Edward G. Robinson and Major Glenn Miller who, with his entire band, had joined the Air Corps and played frequent concerts for AFN from English bases. Actor Broderick Crawford was on the staff. Actor David Niven was on the staff of the combined AFN-BBC-CBC operation. Roy Neal, now NBC news chief in Los Angeles, was there too. Although AFN today prides itself on its objectivity, it wasn't always that way. John Hayes recalls being ordered to play some totally obscure and totally terrible song such as "Lily From Laguna" at a precise time of day such as 1:06 p.m. "Once," he recalls, "we had to play Sur le Pont d'Auignon fourteen times in a single day." No one on the staff ever found out why, but it was obvious they were sending signals to the underground in France or some other occupied territory. By May 1945, shortly before AFN's second birthday, the Russian offensive in the east and the allied offensive in the west led to the surrender of Germany. AFN had grown into a mammoth operation. John Hayes, the young captain who |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It was obvious the Americans were going to be around for a while. Those that had fought their way into Germany from the Normandy beachheads were soon heading home. They were being replaced by new troops arriving overseas for the first time. Like AFN's original audience in the U.K., they were lonely and homesick. A voice from home was every bit as important to them as it was to the earlier audiences.

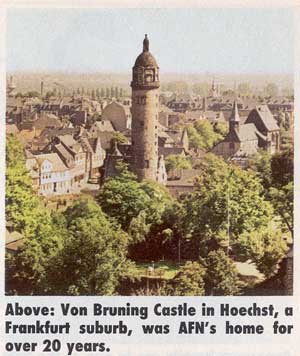

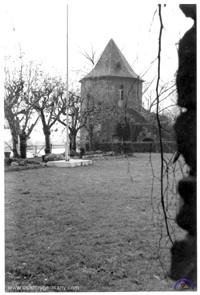

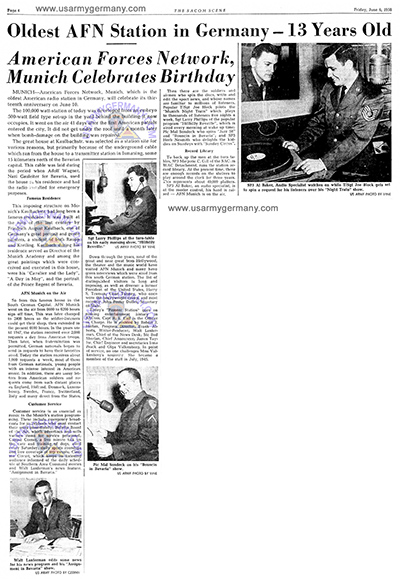

AFN took on the challenge and began to dig in. The first station on the air in Germany was AFN Munich. Its debut was not exactly auspicious, according to its first commander, Major Bob Light. Light, now a prominent Southern California broadcaster, moved his Seventh Army AFN mobile van into Munich on June 10, 1945 and began broadcasting June 11th. He signed on the station the very first morning with a cheerful "This is AFN Munich, the voice of the Seventh Army." Unfortunately there were a couple of details about which Major Light was unaware. One was that the Seventh Army had moved out and General George Patton's Third Army had moved in. Another was that Patton was listening while he shaved. Still another small detail was that the short-fused general lost control of both his temper and his straight razor when he heard that he was listening to the "Voice of the Seventh Army." He lived up to his nickname "Blood & Guts" that morning as the blood streamed down his face and he screamed to his aide that he wanted "that blankety-blank court-martialed." Within a few weeks AFN Stuttgart went on the air although initially it was fed from the Munich studios. The combined power totalled 200,000 watts and because the radio band was much less crowded and average power much lower in those days, this giant voice was heard throughout Europe with ease. AFN Frankfurt, then just another station, began operation on July 15,1945 from a requisitioned house on Kaiser Sigmund Strasse, only a few blocks away from today's headquarters. The staff sound-proofed it by lining the walls with blue-grey Wehrmacht uniform cloth. Before the job was done, the Glenn Miller band showed up to do a concert. It had to be held outdoors on the lawn to the delight of the neighbors and passers-by. In August 1945 both AFN Berlin and AFN Bremen began broadcasting. Berlin is now still very much in operation and still located in the suburb of Dahlem although in a brand-new building especially designed for its combined radio-television program center. AFN Bremen moved slightly north to Bremerhaven in 1949 and continues today to serve the Port City area. AFN Headquarters remained in London at this time, 1945, but when General Eisenhower announced he was moving his headquarters from London to Frankfurt, it didn't take any particular genius on Colonel Hayes' part to know he didn't have much choice but to follow suit. Hayes sent First Lieutenant Jim Lewis to Frankfurt to search for a home for AFN Headquarters. Lewis quickly decided the already overcrowded AFN Frankfurt radio station wouldn't do. By now this facility had moved from its poorly soundproofed house on Kaiser Sigmund Strasse to the Frankfurt Military Compound. Lieutenant Lewis quickly decided this was too close to the flagpole for his rather free-wheeling broadcasters. He realized that it might make the then restrictive non-fraternization and curfew regulations a bit easierto take if the staff could be moved out of the shadow of the highest headquarters in Europe. Besides, he reasoned correctly, being located in a more isolated location might make "drop-in" inspections by the brass somewhat less frequent. In 1945, Hoechst was a comparatively small, quiet village perched on the banks of the Main a few miles downstream from Frankfurt. Dominating the skyline of the village, as it had since medieval days, was the Hoechst Castle. Construction was first begun on the castle in 1356 when Charles IV declared Hoechst a fortified town. It was destroyed by fire in 1396 and rebuilt between 1397 and 1404. In the late 16th century a Renaissance addition was added. It was damaged again by fighting during the Thirty Years War in 1622 and again during a siege in 1635. Perhaps its most famous guest was Napoleon who stopped in on his way home from Russia after his chilly reception there. It passed through many hands over the centuries and in 1908 was purchased by the Count von Bruening from the Prince of Nassau-Usingen. The von Bruenings were still living there in 1945. At least they were until Lieutenant Lewis dropped by in August 1945 on the pretext of a "fire inspection." AFN had found a home and the "castle era," which was to last until 1966, had begun. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

They will talk about the lovely tradition which continues to this day and started with a vow by a local village family that they would offer music from the top of the tower each Christmas in exchange for the safe return of their sons from the war of 1870. They'll remember the long string of anniversary parties held in the castle gardens each Fourth of July. Some remember the memorable interview with King Hussein of Jordan which began "How about telling us, King..."Or the newly assigned officer who met the Beach Boys coming down the stairs after an interview and ordered them to get their hair cut immediately. Memories of Yehudi Menuhin playing his violin in Studio A, of Senator Styles Bridges writing his report on his European visit in a borrowed office and of Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Arsmtrong dropping by for a visit, all are fresh. Celebrities were a common sight during the early occupation days. The war was over, the boys overseas wanted to see shows and the celebrities were anxious to oblige. And, it seemed, they all visited the castle for an interview, a performance or just a short libation in the AFN Club located in the former castle stables. A few of them included Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Dorothy Lamour, Leopold Stokowski and Lily Pons, Eddy Arnold, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Hank Williams and Hank Snow. The list is endless. Mickey Rooney was assigned to AFN for a period shortly after the War. Later Gary Crosby, Bing's boy, joined the staff. The military personnel system failed to assign Vic Damone - instead it had him counting sequins in a Special Services Depot - but he found AFN more fulfilling and managed to spend much of his tour in Europe as an AFN volunteer. Rosemary Clooney's brother Nick and Johnny Cash's brother Tommy both served their military time with AFN. Raymond Burr often dropped in and appeared on the frequent dramatic presentations produced by AFN. So did Vincent Price and even Buster Keaton. Visitors might run across Bill Holden or Jayne Mansfield or General Curtis LeMay or Lowell Thomas or Paul Anka. Mostly though, they would see the staff rushing frantically to meet deadlines. AFN London signed off for the last time on December 31,1945 and, as 1946 began, Germany became the focus of operations. It was necessary to shut down some of AFN's sprawling operations and Colonel Hayes handed the job to a captain named Robert Cranston, his deputy. Soon shut down were stations in Nancy, Dijon, and the Riviera. A few years later, Cranston would reappear. The period between the end of the war in Europe and in the Pacific saw AFN feeding a super-powerful captured transmitter in Munich which served an audience in, of all places, China-Burma-India. Someone then got the idea that China was a little outside the area of AFN's area of responsibility and the transmitter was turned over to the Voice of America. Lieutenant Colonel Oren Swain became AFN commander in 1946 and it fell to him to shape up the "civilians in uniform" who had manned the network during the free-wheeling wartime days. As former staff member Ted Shoemaker says, "They had run a great network but militarily they gave a new meaning to the term "sad sack." Colonel Swain also did some "civilianizing" while he was doing his "militarizing." Talented military personnel were encouraged to take overseas discharges and stay with the network in a civilian capacity. Swain says at that time he was by no means certain AFN would continue to operate for long into the post-war era. Money with which to operate was based on no solid foundation and the military now ran by firm rules, not the "let's do it and worry about regulations later" wartime attitude. Then history stepped in. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With the end of the blockade, the thinking of the Western occupying powers changed; Germany, they soon realized, was an ally. The NATO treaty was drawn up and ratified and, with it, AFN was assured it would be around to play its part in continuing to serve the Americans assigned to the NATO alliance in Northern Europe. Network newsmen continued to cover the major events of the day. AFN microphones were in Bonn for the live coverage of the formation of the West German Government although not much in evidence. Newsman Tom Weriu had neglected to wear the formal clothing protocol demanded and found himself describing events while peering out through a potted palm behind which officials had hidden him. AFN covered the Berlin riots in 1953 and the construction of the wall in 1961. When President John Kennedy made his famous "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech, AFN was there. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The network, which had been shrinking in size, began to grow again with the signing of the NATO treaty. As large troop concentrations were developed, AFN installed stations and transmitters to serve these audiences. AFN Nuernberg went on the air in 1950. AFN Kaiserslautern signed on from a van in an open field in February 1953 and moved into its present permanent home in April 1954. Because so many Americans were stationed in France, which was then a member of the military arm of NATO, negotiations were started with the French government to begin broadcasting from there once again. The negotiations proved to be a nightmare. In those pre-de Gaulle days, French governments came and went with persistent regularity. Negotiations dragged on and it was 1958 before AFN once again broadcast from French soil with small 50-watt FM transmitters at most bases and studios in Verdun, Orleans, and Poitiers.

French sensitivity to the predilection of American comics to poke fun at a nation which, at the time, seemed unable to govern itself resulted in an agreement in the final negotiations that AFN would not broadcast such material. This included a restriction on commentary about France of any kind, even if rebroadcast from an American commercial network. To insure compliance, a French government official was assigned to the network. AFN's return to France was to last only nine years. In 1967 de Gaulle withdrew French forces from NATO control and forbid foreign troops to be stationed inside France. Once again AFN sadly signed off. The final record played over AFN France, according to legend, "accidentally" happened to be titled "Goodbye, Charlie." The equipment in France was packed and moved out, much of it right along with NATO and SHAPE headquarters who moved to Belgium, closely followed by AFN. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On leaving AFN, Cranston was promoted to Colonel and became Commander of the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service (AFRTS) in Los Angeles. Following his military retirement in 1973, he returned to Washington where he became head of the Armed Forces Information Service (AFIS) and continued to direct the activities of military broadcasters world-wide.

On the occasion of his retirement from Federal Service effective April 1, 1983, AFN's Commander LTC Charles R. Crescioni, sent a message telling Cranston he "would always be on active duty with AFN." Cranston replied: "Thank you for your kind message... AFN is my alma mater and I appreciate your offer, which I accept, to always be on active duty... my special thanks to all the staff, especially those who are my personal friends, for the magnificent accomplishments of the network during my time here at AFIS. Bigger things are yet to come... I know that all of you are more than equal to the challenge..." It was during the last year of Colonel Cranston's command that AFN faced the kind of nightmare situation that every broadcaster dreads. November 22, 1963 was a slow news day. At the castle, news editor David Mynatt was getting ready to broadcast "Report from Europe," a roundup of events from around the continent. The regular quarterly program meetings had just concluded and Program Director Don Brewer was hosting the affiliate program chiefs at a cocktail party in the Frankfurt Officers' Club. Also attending was V Corps Commanding General Creighton Abrams. Colonel Cranston was stuck in a traffic jam on the autobahn trying to return to Frankfurt from a meeting with USAREUR Headquarters in Heidelberg. The biggest challenge in AFN's broadcasting history began at 7:34 p.m. when the teletype in the castle newsroom typed out a message: PRECEDE KENNEDY DALLAS, NOV 22 (UPI) - THREE SHOTS WERE FIRED AT PRESIDENT KENNEDY'S MOTORCADE TODAY IN DOWNTOWN DALLAS. "Music in the Air," then one of AFN's most popular programs, was on the air hosted by Sergeant Lloyd Eyre. Specialist Four John Grimaldi, in the newsroom, noticed the wire immediately but because there was no indication of injuries to members of the motorcade, refused to panic and decided to stand by for further developments. They weren't long in coming. At 7:39 the machines typed out: FLASH FLASH KENNEDY SERIOUSLY WOUNDED PERHAPS FATALLY BY ASSASSIN'S BULLET. Grimaldi ripped the copy from the machine and ran it in to Mynatt. AFN policies have always been extremely conservative about breaking into programming for news flashes. Although completely aware of policies and knowing that there would be a regular newscast in 20 minutes, Mynatt didn't hesitate. He grabbed the copy and burst into the "Music in the Air" studio, telling Eyre to put him on the air. At 7:41 AFN listeners heard Mynatt, his voice quivering with emotion, say "Ladies and Gentlemen, we interrupt this program for a special news bulletin. President Kennedy... on a visit to Dallas, Texas... has been reportedly seriously wounded - perhaps fatally." His voice broke as he continued, "We'll have more as it is received here at AFN." It would be days before broadcasting would get back to normal. Newsmen taking their dinner break in the AFN club heard the announcement on the house speaker and rushed back to the newsroom. The Charge of Quarters was trying frantically to reach Brewer and the program staff at the Frankfurt Officers' Club. Cranston heard the news and continued fighting traffic to get back to Frankfurt. A second update came over the wire and Mynatt again pre-empted the airwaves and read a report that both President Kennedy and Texas Governor Connally had been hit. Inexorably the clock continued to move to 8 p.m. when "Report from Europe" was due to begin. No further news came over the wire by 8 o'clock so Mynatt, having no choice, began the regularly scheduled program. As short bulletins came across the wires, Grimaldi ran them in to Mynatt for airing and he interspersed them into the show. When he went off the air at 8:15, AFN had cancelled all its regularly scheduled programming and was not to resume it until after the President had been buried in Arlington Cemetery. Colonel Cranston managed to get through on the telephone which was being blocked by the hundreds of listeners who wanted a personal report on the situation. He ordered up the Atlantic Cable for direct reports from the U.S. and, because in those days the stations normally signed off at midnight, ordered continuous broadcasting. Brewer and his program staff were reached and en masse rushed back to the studios in the Hoechst Castle. At 8:25 a flash came from CBS Radio that Kennedy was dead. Wilhelm Loehr, then as now an AFN music librarian, rushed back to the castle to begin preparing special music programming. AFN newspeople fanned out to gather European reactions for insertion into the continuous news coverage. It was four days of high drama. The arrest of Lee Harvey Oswald. Oswald's death at the hands of Jack Ruby. The funeral. Reports to the public by new President Lyndon B. Johnson. AFN's reputation for fast, accurate and objective news coverage took a quantum leap because of its total coverage of the tragic events of November 1963. Several German newspapers criticized the penny-pinching coverage of the German radio as compared to AFN's. (Nobody could accuse AFN of penny-pinching. The cost of the Atlantic cable was four dollars a minute, a large sum in those days, and AFN stayed with it four days.) The network's days in the romantic Von Bruening castle were numbered. The Farbwerke Hoechst, Germanys giant chemical combine, bought the castle from the Von Bruening family in 1962 and told the Bonn Government it would like to reclaim it for its own use to include a city and company museum. Bonn quickly agreed, as did AFN. While most staff members appreciated the beauty and charm of the castle, no one was so romantic that they would not have preferred a building without creaking floors in the studios, no wintery drafts on the back of the neck and - hallelujah! enough lavatories so no one had to queue up in the hallway waiting for a vacancy. Bonn selected a site next door to the extensive Hessischer Rundfunk facilities in Frankfurt. The choice couldn't have been more fortuitous, at least for AFN. Socially, personally and professionally, the contacts between the two broadcasting organizations have grown steadily, to the benefit of both staffs and audiences through the years. The first set of plans were turned down flatly by the U.S. authorities because there were no outside fire escapes. This was a bit of American quaintness as far as the German designers were concerned. They preferred fireproof construction and fire stairs. Finally plans were approved by both governments which incorporated the latest ideas in broadcast engineering. Costs, to be borne by the German government in return for the right to reclaim the castle, were about $2.3 million. The plans included highly sophisticated soundproofing including burying the studios deep inside the core of the building and mounting them on gigantic springs. Air conditioning for the highly heat sensitive equipment was provided. All metal used in construction was bonded together and completely grounded. Ground was broken in 1964 and in 1966 AFN moved out of its 14th century home and into the 20th century. What the new building lacked in esthetics and romance, it more than made up for in convenience and efficiency. All the speeches at the dedication ceremonies made note of the wonderfully adequate space and the numerous large radio studios-facilities, everyone pointed out, that would be more than adequate for as long as AFN existed. The speakers were partly right. The facilities were perfectly adequate for seven years. Then came television! American television in Europe had actually begun on an extremely limited scale in 1957 when the Air Force installed small black and white transmitters in Spangdahlem, Wiesbaden, Rhein-Main, and Vogelweh which were fed from a studio at Ramstein Air Force Base. It took until 1971 before the first Army installation (at Bad Kreuznach) was able to tie in to the system. From then on things moved quickly. Robert Froehlke, then Secretary of the Army, visited Europe in 1971 and declared that "... the one biggest boost to morale in Germany would be to give our troops and their families American television." This statement set Army wheels in motion and Project J7 (Scope Picture), with the object of expanding television to U.S. Forces in Germany, was energized. Involved in the planning and execution were such disparate bedfellows as USAREUR, USAFE, U.S. Army Communications Command, 5th Signal Command, U.S. Army Television Audio Support Activity, AFN and others. Then Commander in Chief, USAREUR, General Michael S. Davison, gave first priority to the troops in more isolated, forward areas. Next to get television, he instructed, would be non-headquarters units away from major population areas. Headquarters in large cities would be the last to receive it. The first two of these three phases would be handled by the Air Force. Then, as the Army became the numerically dominant recipient of the service, it would assume responsibility for phase three and the operation of the completed network. Transfer of control of television to the U.S. Army - to be operated by AFN was made in July of 1973 as the network celebrated its thirtieth birthday. By then the Air Force had completed Phase II of the Scope Picture expansion with the completion of 46 television transmitters and 64 microwave links. Black and white service was now available to 41 per cent of the U.S. Forces in Germany. Planning and engineering the Phase III installations was complicated by the need to limit signals, as much as technically possible, to troop and dependent audiences only. This had to be done to avoid interference with German TV transmissions and to restrict wide dissemination of programs which are supplied at low cost by the owners for reception by DoD personnel only. In August 1973 it was directed that by 1976 all AFN television facilities would be color-capable. Since Phase III was already designed to accept a color signal, it was necessary to up-grade the earlier phases. While expansion of the television distribution system was going on, the programs originated from rather primitive studios at Ramstein Air Force Base near Kaiserslautern. Programing was in black and white only and transmitted in the European PAL system. This caused numerous problems, not the least of which was the restriction to AFN of more than twenty hours weekly of program material by the owners. They feared the availability of their programs to the general public would work against possible commercial sale in Germany. Broadcasting in PAL also meant persons who had brought their American sets with them from home could not receive the TV picture without set modification. Finally the system was completed. The Frankfurt radio studios had undergone more than a year of reconstruction and modification to accommodate the brand new color television complex. At midnight October 27, 1976, the last reel of black and white film ran through the antiquated projector at Ramstein. Fifth Signal Command crews began the job of reversing the microwave paths so the network could feed FROM Frankfurt instead of TO it. At noon October 28, not without a lot of crossed fingers and eyes raised toward heaven, a camera was symbolically uncapped by AFN Commander LTC Floyd A. McBride, assisted by the USAREUR Deputy Chief of Staff, MG Dean Tice. And, as planned, there was AFN - in blazing, living color. The new color signal was in the American NTSC standard and very quickly programing restrictions were dropped. Within the first color season, AFN was telecasting virtually all of the most popular programs then being seen in the U.S. The assumption of the television mission in 1973 marked the beginning of a period of unparalleled activity for AFN. Succeeding commanders challenged the staff to accept more and more responsibility and provide better and more professional service to the radio and television audiences. It seems self-evident that the staff rose to the challenge. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Under the present Commander, LTC Charles R. Crescioni, the staff numbers about one-half of what it was on AFN's twentieth anniversary. In spite of this dramatic drop in numbers, his staff ... provides a 24-hour radio service instead of 19-hours as in 1963. ... broadcasts a 24-hour FM service in a number of locations, a service which did not exist 20 years ago. ... provides extended television broadcasting from four locations (about 120 hours a month from Frankfurt and in Berlin; slightly less in Bremerhaven and SHAPE, Belgium.) ... provides around the clock news, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. ... produces daily, award-winning radio and television newscasts (with a news staff slightly more than half the size of the 1963 radio-only staff). ... has added a full time radio station (AFN Wuerzburg) to the family of AFN affiliates - without any increase in authorized personnel. ... copes with the greatly increased technical requirements such as maintenance, installation and procurement made necessary by these added services. ... has assumed responsibility for training an increasingly younger staff on more advanced techniques and equipment. ... provides more live radio air time devoted to broadcasting information more needed by the listener than ever before in AFN history. ... attempts to cover activities of interest to the television audience - and does it darn well considering only two, three or (if very lucky) four special events teams daily cover an area larger than the state of Oregon. How does AFN cope with a constantly expanding mission and a constantly decreasing staff? Just like the rest of the military establishment - better planning, better leadership, a sense of dedication, and damn long hours. On the occasion of the network's 40th Anniversary, the staff can look back with pride at the thousands of dedicated men and women who preceded them in providing four decades of uninterrupted information and entertainment to Americans and their families. By turning their eyes to the future, they can see increasingly complicated technology, a continuing need for the services historically provided so well and, more than likely, a mission which will continue to grow. With 40 years of organizational pride behind them and with a half-million viewers and listeners figuratively looking over their shoulders as they work, they wouldn't want it any other way. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

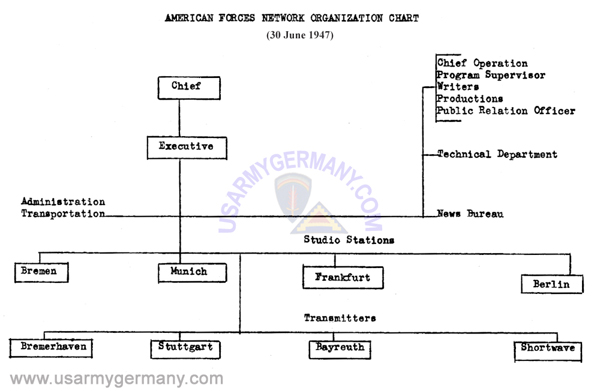

1947 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: Vol IV, The Second Year of the Occupation, OCCUPATION FORCES Series, HQ EUCOM, 1948) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reporting Period: 1 July 1946 - 30 June 1947 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AMERICAN FORCES NETWORK Organization and Staff a. AFN operated the Army-sponsored radio stations of the European Theater, which offered music, news, and other information and entertainment. AFN was directly under the Chief, Troop Information and Education Division, EUCOM, for operations and general policies. The policy of AFN with respect to news dissemination was directed by the Public Information Division. b. On 1 July 1947, AFN had four studio stations, as follows: Frankfurt (key station, 10,000 watts), Munich (100,000 watts), Berlin (1000 watts), Bremen (2,500 watts). It had also four transmitter relay stations, as follows: Stuttgart (100,000 watts), Bayreuth (10,000 watts), Bremerhaven (50 watts), Ismanning near Munich (short wave, 100,000 watts). At the beginning of the period covered by this writing, AFN-Paris, was still operating. c. Headquarters of AFN was located in Höchst in the same building as AFN-Frankfurt. It consisted of the following officers and their staffs: Chief of AFN, Executive Officer, Chief of Operations, Program Supervisor, Technical Supervisor, News Bureau Chief, Administrative Officer, and Public Relations Officer. In September 1946, Maj. William E. Rigel was assigned as Executive Officer to replace the acting Executive Officer, Capt. Alvin E. Orlian. In December 1946, Fred C. Johnstone, Station Manager of AFN-Berlin, returned to the United States and was replaced by Capt. Francis J. Allen. At the close of the period under discussion, the key officers of AFN were: Chief, Lt. Col. Oren Swain; Executive Officer, Maj. William E. Rigel; Chief of Operations, Louis Adelman; Program Supervisor, Keith Jameson; Technical Supervisor, Walter Cleary; News Bureau Chief, William Murray; and Administrative Officer, CWO Charles T. Brown. d. The military and civilian personnel assigned to AFN and the 7706th AFN Company was reduced during the year in line with Theater policy. The Table of Organisation authorized the following: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

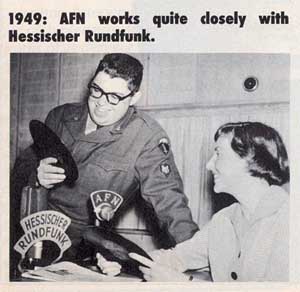

The 7706th AFN Company Policies b. During the summer and fall of 1946, AFN "slanted" an increasing number of Its programs toward the interests of dependents and American and Allied civilian employees. Broadcasts designed to interest these groups included "It's All Music," "The American Word," "It's a Woman's World," and "International House." c. Late in 1946, AFN began cooperating with various foreign broadcasting systems with the aim of bringing some phases of foreign culture to its listeners. For that purpose, lines were established to the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, and Sweden. Typical of the resulting broadcasts have been a special broadcast from St. Peters Cathedral in Rome on Christmas Eve 1946, and programs of folk and classical music from Prague. Closing of AFN-Paris The Setting Up of "Short Operation" Systems |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1949 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

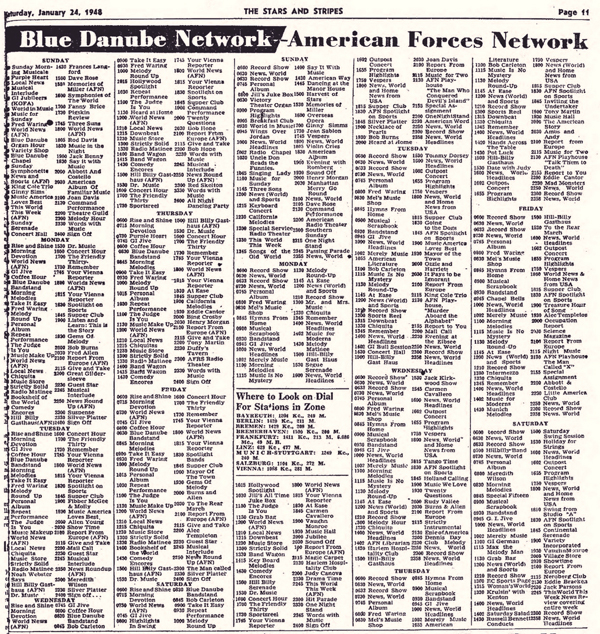

(Source: STARS & STRIPES, July 4 1949) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Headquarters AFN-Europe and the Frankfurt AFN Studio have been operating out of the Von Bruning Schloss compound in Höchst (near Frankfurt) since early 1945. In 1949, AFN - a part of the Army-AF Troop Information & Education Division, EUCOM - has five studios: Transmitters are located in: Presently, there are 92 enlisted men working at AFN, including announcers, newswriters, actors, engineers, librarians, and sound technicians. (Webmaster note: in addition to the EMs, there are US Army officers, US civilians and German local nationals working at AFN-Eur.) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

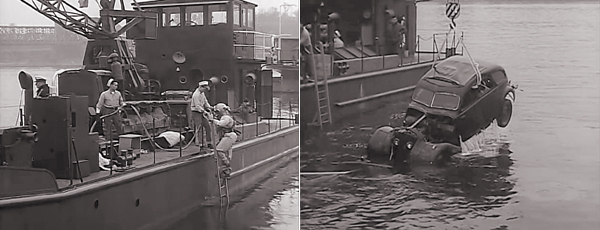

The recovery of a US Army sedan that crashed off of a bridge in southern Germany and is recovered by divers of the Rhine River Patrol is covered on-the-spot by an AFN reporter |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the AFN station, technicians keep open the channels which carry the reporter's first hand account of the recovery operations at the accident scene |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The AFN-Europe network operates similar to any good-sized network in the US -- minus advertisement and singing commercials. AFN receives through the Armed Forces Radio Service in New York and Los Angeles the best radio shows in the nation. During the baseball season, a game is piped in from the US in "live" every week. AFN announcers and their portable microphones cover every phase of the occupation -- in the field with troops on maneuvers, EUCOM sports events, speeches by US High Commissioner John J. McCloy and many other speciel events. Through three wire services (Associated Press; United Press; International News Service) it also keeps EUCOM listeners informed on happenings the world over. In the past year, AFN-Europe has placed increasing emphasis on "local production" from its own five studios. Some outstanding examples are network programs such as "Music in the Air," "Man to Remember," "Take 10," and "Hill Billy Gasthaus." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1951 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: STARS & STRIPES, July 4 1951) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AFN-Europe, currently directed by Col Philip M. Johnson with Lt Col L.E. Gaither as his executive officer, is on the air from 6 am to midnight -- 126 hours of weekly broadcasting. About 80 percent of the programs are network feeds (recorded Stateside shows). The remainder consists of locally (AFN-Europe) produced programs and special news events. AFN-Europe has a staff of 136 soldiers and civilians and comes directly under the control of the Armed Forces Information and Education Division, EUCOM. The staff consists of 35 civilians, 95 enlisted men, one WAC, and five officers. 23 AFN transmitters scattered throughout the US Zone beam programs to the EUCOM audience. AFN programs originate from six major studios: Chief of Operations is Louis Adelman; programm director is Emil Schwetzer. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AFN Headquarters building and Schlossgarten, 1959 (Frank da Cruz) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1959 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: Email from Frank da Cruz, dependent, Frankfurt, 1958-61) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

I actually "worked" at AFN Frankfurt in Höchst for two years on the "Teen Twenty" show and learned all about radio. I also had my own show in the 97th General Hospital closed-circuit radio station. The decorative motif in the

hospital was swastikas, millions of them. Click here to see additional Frankfurt fotos and comments by Frank. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

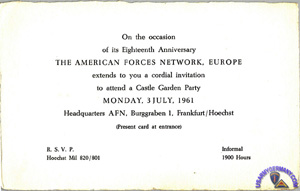

1961 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: Invitation to Castle Garden Party, 18th Anniversary of AFN in Europe, 3 July 1961) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: YouTube website) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1986 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: Email from Jim McKane) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

I was stationed in Germany at both HHC, 294th USAAG in Flensburg and the 75th USAFAD when I was 20-21. I arrived in Oct 1982. It was my first unit in a 21-year career.

I later went back in 1986, but to Frankfurt for another 10 years. My promotions from E1-E6 were in Germany - Flensburg 1982-84 and Frankfurt/Heidelberg. (I was stationed at Fort Campbell, KY 1984-86 and spent 3 months at Fort Ben Harrison, IN, before returning to Germany as a Broadcaster.) I made E7 in CA after tours to the USARC in Atlanta, GA then, and did my last 3 years in Hawaii at Fort Shaffer where I made the E-8 list before retiring. While in Frankfurt I worked with almost all the units thru my assignment with AFN Frankfurt Local, and HQ, AFN Europe. I was one of the primary Broadcasters from 1986 thru 1991, and remained supporting AFN while I was assigned to the 7th ARCOM near Heidelberg from Dec 1991 thru Oct 1996. I started working as a Projectionist at Fort Campbell. When I PCSed to Frankfurt, AAFES found me and put me back to work at the Idle Hour in Frankfurt, next to Frankfurt American High School. I eventually managed all 16 Theaters that operated in Frankfurt, Bonn, Hanau, Friedberg, Buedingen, Wiesbaden, Rhein Main, Darmstadt & Babenhausen. I visited numerous others over the years. (The theaters at) Drake Edwards & Camp King closed in my early years at Idle Hour. We renovated Idle Hour in 1989-1990. It was built originally by Hitler's military in 1939. The Abrams Building and Frankfurt High School also were renovated at the same time. I left the Active Component and went to US Army Reserves, and full time managing theaters in Dec 1991. Later theaters transferred from the Services Dept of AAFES to Food (Department), becoming Food and Theater. I would additionally manage the Frankfurt High School Cafeteria and all Elementary School lunch programs, Middle School Cafeteria, Abrams Snack Bar and the last Burger Bar in Frankfurt, at Gibbs Kaserne. I closed it and the Gibbs Theater in 1994; the Idle Hour Theater, completely paid off, in 1995 and was at the Hauau Cafeteria location where we had a couple food facilities where I managed remaining theaters until leaving Germany for Vandenberg AFB, CA in 1996. I worked in a small Public Affairs Detachment that deployed with V Corps PAO in Dec 1995 to bridge the Sava River into Bosnia on IFOR, and returned from Hawaii to rotate on SFOR in 2002, supporting Bosnia and Kosovo. I operated the FM Automations at AFN from 1987-91. On 01 April 1989 we signed on "ZRock" in Germany at noon, creating the very first FM Broadcast Network throughout Germany. It would later become ZFM in 1990 joining the remaining FM Affiliates which used to just simulcast their sister AM Stations at the start of the 1st Gulf War. It would broadcast live through the War from our FM Studios out of Frankfurt for the first time. I would (have continued to) operated the FM Automation but they build a brand new Radio Master next to TV Master Control and I sadly decided to leave AFN after all those years at the end of 1991. For 6 months I did the Morning Show on AFN Bremerhaven on Carl Schurtz Kaserne in Bremerhaven in 1983 and later returned to the 75th (USAFAD) and was released on weekends to AFN Bremerhaven until I left Germany to do Saturday Radio shows and enough spots & features to stay on air all week. I broadcast live outside in front of all Northern Germany at the Frankfurt American-German Volksfest during my last two weeks in Germany in 1984. It was bliss!! My sister broadcaster, Cindy Dall, now also lives in San Antonio and she and I would broadcast live for the first time as a team my last two days/nights in Germany. I later did TV News in 1986 after arriving back in Germany until I started "Morning Drive" on America's largest AM station, AFN Frankfurt, 150,000.watts. My cousins used to listen to me when they were stationed with the Navy in Scotland when I was on the radio those years. I did the Morning Show for one year. Most only lasted 6 months due to burn out.... I had the time of my life! I went to TV Promo for 6 months becoming the voice of AFN TV in Europe before transferring back to Radio, this time Network Radio. I did live shows daily on FM, did the work recording all initial FM Music on 4-Track Reel to Reel TEAC machines I purchased (I still have one) for the FM Network Start Up, and started an AM Network Country Show - we aired in afternoons called AFN Country Roads which I did right up to leaving AFN Europe from Active Duty. The first year and a half FM was automated, I was the Voice of Z-Rock. I wanted to return later to work in Network Radio as a civilian... But it never happened. Oh, almost forgot, I did "Tonight At The Movies" for nearly 10 years... Which proudly made it on AFN's 60th Anniversary CD. I created it when I arrived at AFN Frankfurt in 1986. Knowing and having the insight of AAFES Theater Circuits and how they worked... I would stay up to date with the many of the Motion Pictures. I had a friend at the Giessen Film Depot, where all films entered. AFN Affiliates always did Club and Theater readers. We trained on them in DINFOS (Defense information School) as Basic Broadcasters in our AIT. However, AFN Frankfurt had never done them with 42 sub communities. I could be wrong, we may have gotten to 48. So I was tasked to come up with a way to get weekend movies into a 3-min feature while my counterpart put together a Club Update. I originally called it "This Weekend At The Movies." In the month I started a 58-sec Spot "Tonight at the Movies" that had a very ear grabbing audio production music with my "Tonight at the Movies." My years with AFN and Idle Hour which I managed 8 years...were some of the best in my life. Many times over I wish they had lasted forever. I would manage & renovate Food Courts & Restaurants, manage & renovate theaters for AAFES until retiring in 2012. Combinining Army & AAFES, I invested 49 years of service to my Country by the time I was 50! That's not counting a year I worked for MWR in Rec Centers at Fort Campbell before Theaters. That would make 50 years!! I plan to create a Theater Web Page or FB page which is much easier... As I keep finding former Theater Employees, all of which were Active Duty or Dependants operating them at one time. I just found another on Facebook that managed 3 Theaters in Hanau originally for me I believe while I was closing the Frankfurt facilities. After WWII, The Army and Air Force Motion Picture Service was not only the highest source of income for Hollywood, they were the only world wide Theater Chain. They were all originally operated as Units with a 1LT to Capt depending on its size and operated with enlisted. Some Navy, Marines and Coast Guard Theaters are still operated with Active Duty today. MWR took over in the 1960-70s all Army & Air Force Theaters, some Navy. Then they couldn't compete with Videos, AAFES took the Army & Air Force Theaters over in the 1970's & early 80's. I started working at a couple of the last two that converted at Fort Campbell: Wilson and Mann Theaters. We even played different movies for different audiences back then, as the Wilson was older and by the PX. It showed "G" Matinees Saturdays & some Sundays and some were old Disney, Shirley Temple, Lassie Films that actually had crowds. Many films were difficult to show and needed a lot of preview work splicing and repairing sprockets. The Mann was a 1,000 seat Theater in the middle of the Troop Division Barracks and showed "R" rated films. We even showed "X" rated movies that were torn up as late shows on Friday Nights. We (Projectionist) hated those as they only had so many and were brittle films running thru the 1930's Peerless Carbon Arc Lamphouses & 1940,s Simplex Projectors. These were worse to run than the "G" movies at the Wilson. I trained & hired at Wilson, transferred in 4-5 months to Mann. We were still using Carbon Arch Lamphouses that dated back to silent films.. They were all replaced by the mid 80's. We already were operating Dolby systems and I had the very first in Frankfurt, the CP50. There is just so much history I want to protect as these Military Treasures are slowly declining, being only 1 % of Hollywood revenue in the late 90's. We had over 3,000 theaters in the Army & Air Force after WWII, and close to 900 were in Europe alone. Then you had some military installations in the US that had 5+, and of course the Pacific Theaters. By the time I came to Frankfurt only around 300 were left in Europe. Today there may be 12. I believe we may have no more than 50 World wide and COVID still has over 50% shuttered. I want to do something to celebrate 100 years of Military Motion Pictures, Europe being a major role in that... As I will be 80 when by the 2040's they will be that old, I have a good 20 years to do the research and have tons of pictures... I may try to collaborate with Military, MWR and AAFES Historians to write a book. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1945 - 1993 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: "50th Anniversary, AFN", AFN TV-Guide, July 1993) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AFN Affiliate Stations in Germany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

AFN

BERLIN

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When the airlift ended in 1949, AFN resumed its 19-hour schedule.

Then, in the 60s, the East Germans began broadcasting an English

language propaganda program called "Berlin International" which

they put on AFN's frequency the instant the station signed off.

Visiting officials from Washington heard tapes of this anti-American propaganda effort and ordered AFN Berlin to stay on the air around the clock. The station has reported history in the making. Stories covered in depth include the East German uprisings in 1953, the construction of the infamous Berlin wall in 1961, President Kennedy's "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech in 1963 and subsequent visits by Presidents Nixon, Carter and Reagan. Almost every world figure to visit Berlin faces an AFN microphone or camera. Today AFN Berlin is located in one of the most modern radio/television facilities in the world. Located across from U.S. Army Headquarters, Berlin, at 28 Saargemunderstrasse, the AM-FM radio portion of the facility has two stereo studios, two mono studios and a news studio. The TV studio can accommodate six separate sets and is equipped with three color cameras and the latest video control equipment. AFN Berlin serves a community of about 15-thousand U.S. military members and their families. Major units include the Berlin Brigade, Field Station, Berlin and the 7350th Air Base Group at Tempelhof Air Base. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AFN Bremerhaven building mid-1980s (Mike Thompson) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By

October 1948 the majority of the listeners were in Bremerhaven and

the station moved to Building 2, Carl Schutz Kaserne. A 1-thousand

watt transmitter occupied the basement. This was soon moved to the

dock area where it remains. In 1962 the station moved to Building

1 where it still is but the power of the transmitter was increased

to 5-thousand watts. On 21 August 1979 the station began transmitting

to troops in Osterholz-Sharmbeck on FM 92.9 MHZ.

One month after its 30th birthday in 1975, AFN Bremerhaven became the first of AFN's color television stations. The AFN Headquarters in Frankfurt was still converting its building to accommodate color. Bremerhaven signed on with color TV on 25 August 1975. Once again staff inventiveness paid off. Although not designed to do "live" television, they wanted to produce local interviews. Unfortunately there was no room big enough for guests AND a camera. The inventive solution? Put the guests in the studio and the camera in the latrine across the hall. Things have improved considerably since that primitive beginning but AFN Bremerhaven continues to serve well its radio and TV audience in Norddeutschland. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

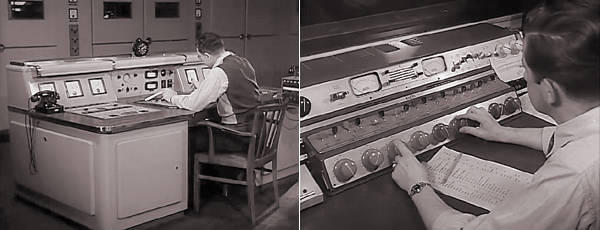

TV Master Control, AFN Bremerhaven (Mike Thompson) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mike Thompson, a former AFN'er stationed in Bremerhaven, was a Radio/Television engineer at the AFN station from 1985 to 1987. Mike has created a web page with a nice collection of photos from that time. To view his page click here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1955 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: Email from Glen "Glee" Duff) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

I served on AFN Bremerhaven during the hight of the Cold War (1955-6). As Specialist Glen Duff, I had two network shows (Sunday Syncopation and Off the Top Shelf) as well as the local 5 o'clock club. Program Director was a great guy and friend by the name of MSGT Hal Tattle. We had a really good staff including a DA Civilian News Director by the name of Dick Knowles, as well as some great and fun on air talent. Wish I could remember all their names. Bob Ramsdell, Ralph Crane, Al Woods. The station had a first lieutenant as OIC, but was really run by another great guy by the name of MSGT Tom Dolbow. While there a new announcer was sent up to us from Frankfurt, who brought a German girlfriend with him. They lived off base. She was super inquisitive about the mechanics of the station and it's hard-line phone connections to all the other stations on the network that I became suspicious. I mentioned some of her actions to an OSI friend of mine and she was gone within a week. A spy? We'll never know. Anyway, it was an interesting two years which I'll never forget. Retired now, living in the Fort Myers area. I spent the rest of my working life in the field of communications. Couple of large ad agencies - owned my own station once - owned my own agency - but all the time a worked off and on on radio, even down here in Florida. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: Email from Alan Herbert, AFN Bremen 1946-1948) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bread, Butter and Coffee (Originally, Herbert was assigned to a unit in Stuttgart) In June, 1946 we were located in a small compound, which also contained an Army coffee roaster and bakery. The delicious smells would reach a point where we couldn’t stand it. We'd go down and get some fresh coffee, a loaf of bread and a pound of butter and have a feast in the office. The loaves were round, as big as a wheelbarrow wheel with a half inch thick crust. My mouth waters every time I think of that bread, but it was only good when it was still hot. The Red Cross Does me a Favor |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Although the story of AFN Frankfurt parallels that of the network,

the station started out as just one more outlet. At the end of the

Spring offensive in 1945, AFN moved into Germany with the troops

and set up radio operations in Frankfurt, Munich, Stuttgart, Berlin

and Bremen.

Opening day for the Frankfurt station was July 15, 1945 and the first studios were in a residence located only a few blocks from its present home. When General Eisenhower selected Frankfurt to be his headquarters, AFN did the same and the Frankfurt station took on a new importance. When the network headquarters moved into what was to be its home for twenty-one years, AFN Frankfurt moved right along with it, into the von Bruening castle in Hoechst. In 1966 the Castle era came to a close. The new headquarters was completed at Bertramstrasse 6, next door to the German radio and television studios of Hessischer Rundfunk and across the street from the Frankfurt Exchange. Once again, as the headquarters moved, so did the Frankfurt affiliate - this time to an ultra-modern facility with eight, count 'em, eight studios. This idyllic state lasted until 1976 when television moved in to share space. Four of the original radio studios are now dedicated to television operations. The remaining studios still serve as mono- and stereo-recording, production and broadcasting studios. FM became a reality on November 12, 1973 and this second stereo service is now heard from a powerful transmitter located on top of the Feldberg, Hesse's highest mountain. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Source: Email from Julie Kelly, daughter of the late Gilbert Gass, AFN Frankfurt, early 1950s) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The station

also feeds its programming to audiences in Bitburg, Pruem and Pirmasens.

It is also heard, on a limited scale, in AFN's ancestral home in the

United Kingdom. The signal is transmitted to a number of American

air bases in England by way of tactical circuits and put on closed

circuits there to various clubs, shops and messes. Service originally was only on the AM radio band. But in recent years, 26-year veteran engineer Johann Huber and his engineering staff have installed 24-hour, fully-automated FM stereo with transmitter at Pulaski Barracks. This offers alternative programming to the giant audience in the AFN Kaiserslautern listening area, which also includes USAFE Headquarters at Ramstein Air Base. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The station has been housed from its very beginnings in the former

mansion of famed German artist Kaulbach. As the station entered

its thirty-eighth year, AFN Munich was getting ready to move to

a new home just up the street.

The new facility will have everything the original home had, except thirty-eight years of memories ... memories of daily programs like "Bouncin' in Bavaria" and the noon show with the title that always gave local German listeners a chuckle "Luncheon in Munchen." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1958 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| That's today.

But back in 1949 there was no studio in Nuernberg - only a transmitter

fed from the Munich station. For reasons lost in the mists of time,

the transmitter was in the tower of the Faber Castle and the antenna

was a wire running down to a water faucet in the yard. It worked fine,

although it shouldn't have. The station's first birth was January

28, 1950, when studios were opened in the prestigious Grand Hotel.

(When the local Commanding General threw the switch, he didn't know

the switch had been purchased on the black market for two pounds of

coffee. Neither did the AFN management until 1983, when the perpetrator

admitted his "crime" as he retired.) Again, for reasons not quite

clear, the upside-down antenna was moved in late 1949. This time the

ground system was a metal web on the bed of the nearby Pegnitz River.

But by mid 1956. the owners of the fancy hotel which then housed the

station indicated they'd prefer a quieter tenant, and again the station

became a satellite of AFN Munich. It was reborn a second time when the sergeant in charge of the underwater transmission system discovered the unused space on the top floor of the Bavarian American Hotel. Permission to build studios was granted, money secured, construction completed and the station reopened May 18,1960. It is still on the air from the same location, staffed by totally dedicated broadcasters. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AFN Stuttgart top floor of the Graf Zeppelin Hotel, downtown Stuttgart, 1950s (German postcard) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AFN Stuttgart (on second floor of the Stuttgart Elementary/Junior High School), 1984 (Ed Ewing) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

AFN

STUTTGART

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The facility

consists of two on-air studios, one of which is stereo. There is also

a stereo production studio, a master control, FM automation area and

a large record library as well as administrative and technical offices.

In October 1970 FM became a reality in Stuttgart, first in mono and, in 1972, 24-hour stereo. FM is on 102.4 Mhz, and AM is transmitted on 1142 Khz with 10,000 watts. AFN Stuttgart also feeds transmitters in Mannheim, Heidelberg, Karlsruhe, Goeppingen and Ulm. Although television is not originated from Stuttgart, the station is a part of the AFN TV system. The staff has been trained to produce television stories and has its own Electronic News Gathering (ENG) unit which it uses frequently to cover important events in the area which are sent to Frankfurt for telecasting throughout Germany. Important organizations served by the Stuttgart station include EUCOM and VII Corps Headquarters, USAREUR Headquarters, numerous units of the 1st Armored Division and VII Corps Artillery plus the many support units in the Baden-Wuerttemberg Support District. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1964 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: STARS & STRIPES, March 18, 1964) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AFN Stuttgart recently celebrated its 16th anniversary of broadcasting service. Originally set up with a skeleton staff and a room in the downtown Graf Zeppelin Hotel as its only studio, the AFN outlet now occupies spacious studios in Robinson Barracks and broadcasts an average of four hours daily of locally originated programs. The present staff numbers 19 and is headed by Capt George Kaso. AFN-Stuttgart programs are broadcast from three AM transmitters (Hirschlanden, Ulm and Goeppingen) and one FM transmitter (Frauenkopf). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1969 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: STARS & STRIPES, Dec 2, 1969) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AFN Stuttgart is located on the second floor of the American Elementary & Junior High School building at Robinson Barracks. The studio is normally off limits to the students except for once a year when the staff give a tour of the facility to students curious about the AFN operations. The AFN station provides about 70 hours of local programming a week for both AM and FM outlets. The station recently launched a schedule of double programming to give listeners a choice between regular shows (on AM) and more refined music on FM. Capt Richard A. Ost has been the Station manager since February. Thomas B. Smith is civilian director. Other members of the staff include SSgt Tom Tucker (chief announcer and host of "The 1605 to Nashville" program, country & western music); Spec 5 Patrick Brown (news, jazz, and the "Noon-Day Shopper" program); SSgt Roy Cooler (chief engineer); Spec 4 Gary Thompson ("Dawn Patrol," the wake-up program in the mornings); Ms Margret Reich (works the radio control board); and Jo Chen (production technician). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Within the network,

a monthly competition for the best spot announcement was won three

times in 1982 by Wuerzburg, including Spot-of-the-Year. All of this was done by a station so young it still has one of its original enlisted members on the staff. For many years Marneland - Wuerzburg, Kitzingen, Wertheim, Giebelstadt, Schweinfurt and Bad Kissingen - was served from the AFN studios in Nuernberg. Because of the distances involved, it was a difficult situation both for AFN and the 3rd Infantry Division. It took a lot of coordination - and cooperation - between the Division, the AFN Headquarters and USAREUR Public Affairs officials but without adding a single person to the network, it was possible by borrowing a Sergeant here and an SP4 there to get a staff together. Other affiliates and the Headquarters in Frankfurt were able to find enough equipment to get started and - on 1 May 1980 - there was a new baby in the AFN family. SSG Clark Taylor transferred to Wuerzburg from the affiliate in SHAPE, Belgium, and became one of AFN's first enlisted station managers. Today this slot is filled by SFC Mike Pervel, back with AFN after a tour earlier at AFN Munich. The old-timer on the staff is SGT Mike Anthony who was there the day the doors opened for the first time. Today he is broadcast supervisor. AFN Wuerzburg is still too new to have built up legends such as the other stations have - but it's working on them. Already the staff is looking back on the time they had an official leprechaun appointed for a "Luck of the Irish" contest. And the time the staff delivered singing Valentines. Or the "DJ for a Day" contest. The baby looks like it's going to grow up to be a pretty good kid! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This is AFN ... a quick tour in 1983 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Source: "40th Anniversary, AFN", AFN TV-Guide, July 1983) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MISCELLANEOUS AFN Moves to Mannheim -- After six decades of broadcast service to troops in Europe and beyond, HQ American Forces Network moved its operations from Frankfurt to Mannheim in October 2004. (See related Stars & Stripes article) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related Links | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||